On Writing ‘The Somnambulist Cookbook’

by Andrew McDonnell

The dead are too busy to haunt us. If you follow Jung on life after death, he suggests that they stand behind our backs seeing how we develop, as if by being dead they have stopped being able to learn from existing, stopped from understanding why exactly we are here, and who we are today.

My father is standing behind me. It is the day after my book is published. I’m reading poems from the book and its Father’s day. He is leaning in, sharpening his ears to every cadence, half-rhyme and dissonance.

He didn’t live long enough to see my book, passing away in March 2017 at the age of 83. What I learned from that loss, among a great deal of things, was that my love of storytelling, of capturing moments was from him; I realised this as I wrote his eulogy. I also learned to get a move on.

He lived in the same house, in the same village, from birth until death. He knew what the sound of Doodlebugs was like, he knew the feel of hot air blowing in through the net curtain from a barrage balloon exploding, and he experienced a village change from generations of families to outsiders. He would tell these stories again and again, each one a slight variation on the former, honing it each time until the story was almost flawless. Yet he was never nostalgic, not fully, though he loved the vintage tractors he worked with as a farm labourer in his youth and he loved steam engines, he managed to also see that change was inevitable and that history repeated itself – that the warnings are always there, and it is the great nostalgic shits of history (for what is Nationalism but the most cancerous form of nostalgia) that destroy us. Mr Farage being such an example of the movement to get ‘our country back’ whatever ‘our country’ was; possibly one of Rickets disease and poor life expectancy.

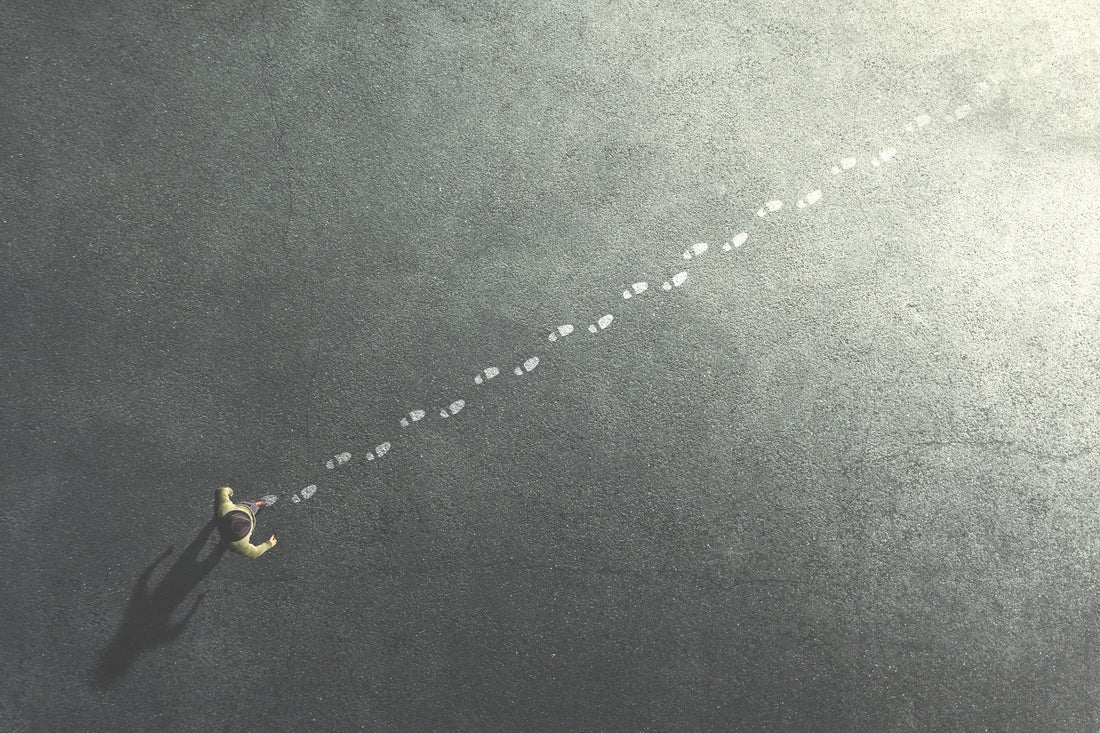

I understand Jung when I think about it in these terms. We are a species that is generational, and like Macbeth seeing the seed of Macduff stretching down the decades, it is foolish to meddle with such a successful business model. One of the sharpest stabs of grief was the realisation that no one stood between me and death anymore. I have my own son and daughter to now stand in front of, knowing that their first steps will eventually be the steps towards burying me. I’ll then stand behind them.

* * *

What does any of this have to do with The Somnambulist Cookbook? Well it is about that attempt to get as near to a truth as possible. The thing I was trying to capture was the truth of disappearance.

It’s always struck me that missing persons cases resonate with us as fundamentally there is a mystery to be solved, and everyone loves a mystery. If we only listened to the six o’clock news, we might deduce that the way to find a dead body is to be a dog walker. Bodies are never found by dogging parties, or people at an illegal rave. It’s always a solitary dog walker.

Walking uncovers a lot of things, and what do we make of that most unnerving of peripatetic activities, somnambulism?

What is the sleepwalker but a more honest version of ourselves? Free from the conscious manipulation of our waking hours, free to wander the margins of the unconscious, like a clichéd zombie doing the things it used to do when it was human, the sleepwalker is pure routine. For me, poems, like somnambulists, are the middle of a Venn diagram. The action of writing poems has always been some sort of deal between the conscious and unconscious mind. A place where we know that truth is not something concrete and fixed, but something fluid, ambiguous, multi-faceted, sometimes contradictory but ultimately not false. It can be touching, sad as fuck, angry or funny. It can be all those things at once. This is what I learned from loss and this is what the book explores – the sense of things constantly disappearing and changing and at some point accepting that nothing and no one is fixed.

The Somnambulist Cookbook by Andrew McDonnell is available now.