The Future of Novels in the AI Age: How AI could reform or replace writing as we know it

By Chloe Birch

The novel has forever been shaped by the tools and technologies of its time, from the printing press to the word processor. But now, a new force is making itself known in the world of fiction: artificial intelligence.

Nadim Sadek from The Bookseller, considers AI to be ‘a fact of life. And a fact in publishing’, but how much is it changing the landscape for novelists and authors? And what exactly does the future of the novel hold?

In an attempt to explore these questions, I talked to three Salt authors: Vesna Main, Nicholas Royle, and Alice Thompson, about their feelings regarding AI and how it might affect the literary world.

Using AI to write

As AI meshes with the world of literature, one of the most contentious issues to emerge is the use of generative content tools like ChatGPT to create ideas, plotlines, and even text itself.

The ability to use such tools in this way could, of course, threaten the creativity of human authors, being cheaper and faster to produce. For Vesna Main, the prospect of AI creating primary content is deeply unsettling: “I imagine it is likely that one day, and soon, alas, AI will be genuinely creative and produce literature, the writing that I would consider art,” Main said. “For me, what makes us human, and helps many of us carry on, is precisely this privilege to struggle to be creative. Without it, the prospects are gloomy for people like me.”

Alice Thompson shares the anxiety of AI changing the economic picture for authors like herself and Main. She says: “As AI writing becomes more profitable for publishers, and the operation runs more smoothly in terms of writing and publication, traditional writing will be eased out. It will no longer be profitable for writers to write.”

But while AI may be able to turn out a book, Nicholas Royle still feels works created by computers may lack something. Speaking about people replacing creative writing with AI, he said: “They might succeed in establishing themselves as authors, but they’ll never be writers, in my opinion.” As he sees it, writing is rooted in qualities a machine cannot replicate: “Craft is vital, and lived experience is at least a desirable part of the defining characteristics. Emotional resonance too”.

However, Royle finds the act of using AI as a research tool “reasonable and not very different from using Google” but restates his belief that it is unsuitable for use in creating fictional work, expanding on his opinion that craft, lived experience and emotional resonance are all “lost” if AI is to be used in, or used to replace, the creative process.

AI as a personal assistant

AI can be used for far more than just generating stories. Rather than posing only a threat to authors’ jobs, it has potential to handle time consuming tasks like editing, research, and admin – freeing the author to devote more time to creativity and writing.

Main recognises these benefits, joking that it could also provide emotional support when writers are faced with rejection.

Despite those perceived positives, Royle and Thompson both struggle to see how they would incorporate AI as a personal assistant in their everyday work, with Thompson finding that technology “creates as many problems, with all its technological glitches, than it solves.”

The idea of using AI as a research tool, for example, using it in place of visiting a country in order to write a book set there, received a mixed response from the authors.

While Thompson remains unsure, Main claims that this is the “legitimate use” of AI. However, she adds that “what matters is imagination and in future, AI will have that too. There are plenty of genres, such as historical, sci-fi, fantasy, where no one has been there.”

Meanwhile, Royle emphasises that while he doesn’t want to “dictate how other writers work”, writing a novel set in a place he hasn’t visited himself is not for him. He further states: “It doesn’t make me want to read a novel if I know the author has not lived in or at least visited its setting.”

He added, however: “I think there’s a huge difference between this and someone asking ChatGPT to write them a story about X, Y, or Z.”

AI replacing human authors

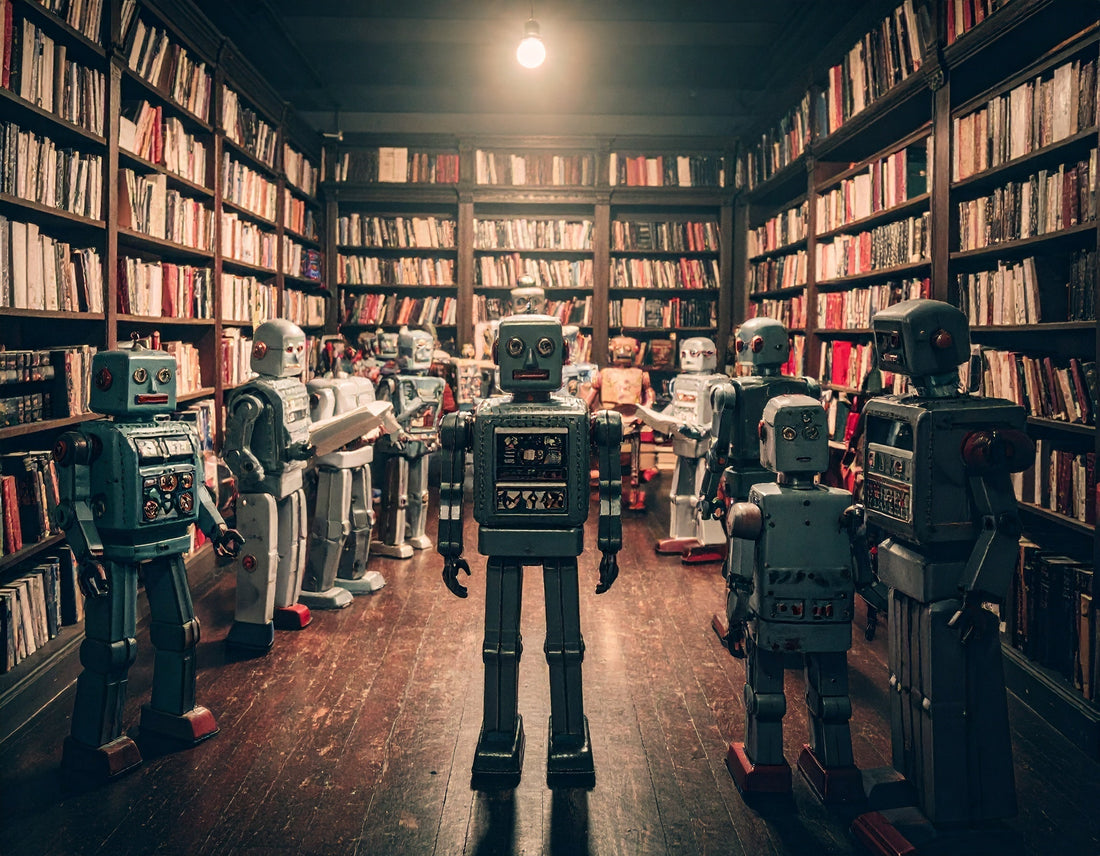

Much of the anxiety around AI’s capacity to write books arises from fears that human authors could be sidelined, leading to a future of bookshelves dominated by AI-generated literature.

With Phillip Stone, the head of publishing account management at NielsenIQ Book Data, claiming that it is likely AI will produce a bestseller by 2030, the question persists, would readers care if their books were written via AI, if the book was of good quality?

Main considers this a “scary, nightmare of a future”, adding that despite the fact that AI is probably already being used to produce genre literature; she is doubtful that, at the moment, it can write literature as art, that is, literature that leads to new directions in writing.

On the contrary, Thompson believes that the chances of an AI-written book being very good are high, commenting further that “it will, after all, have been trained on all the great literary masterpieces of the world from the beginning of the printed word.” However, she voices concern that this will render writers “redundant”, claiming that the use of AI in literature is “threatening our (all humans) humanity, which literature explores and embodies.”

The idea that AI is trained on pre-existing works of fiction raises the question of whether or not it can convincingly mimic any author’s writing style, or if it lacks the emotional depth and personal experiences that make a truly authentic piece of work.

Royle claims he would care greatly if the books lining his shelves were written using AI, and when it comes to whether AI can replicate a writer’s personal style, he admits he’s heard it’s possible but has “no desire to find out if that’s true or not.”

By contrast, Thompson takes a more confident view, arguing that AI could replicate an author’s style easily: “Writers have assimilated all they have read; so will AI. It can be programmed with a personal style”, adding that “writers are all trained on the past too”.

Main offers a sceptical, but cautious, perspective, as she admits that many writers, mostly commercial ones, lack a truly distinct personal style anyway: “Most popular, best-selling stuff, can be imitated and produced by AI.” Further stating that in what she sees as a “nightmare world”, we may see original content written by AI, less Dickensian, and more “AIesquian”.

She even experimented herself, asking AI models to “write in the style of XY, and even in the style of Vesna Main”, but found that “the result was puerile, a style superficially recognisable as the writer’s since the machine picked out what it thought were defining features of the style and inserted them into the story.” For now, she concludes that AI’s mimicry remains “not very clever, but it was fast.”

The rise of AI in literature compels us to rethink the essence of storytelling, and how the collaboration, or potential competition, between human and machine may redefine the boundaries of artistic creation. Authors like Thompson, Royle, and Main illustrate a range of responses, with some cautiously embracing the potential of AI, and others wary of its effect on the author’s creative process.

AI is reshaping the novel’s future, and with it, the very nature of storytelling itself.